How did you discover your love for music? Did your surroundings effect you in a way?

Music became important to me quite late. Until the age of 14 it played only a marginal role in my life: As a child, my parents took me to classical concerts and operas, but I do not remember them influencing my life (on a deeper level, of course, they could have). I also did not really have my own taste in pop music, like some of my friends. The defining moment came on my fourteenth birthday: my grandmother, who had been born the same day as me 49 years earlier and played the piano beautifully, taught me a little four-hand piano piece to play for the family. If I were religious, I would say it was a revelation. From then on, music became extremely important to me. I started learning the piano, formed rock groups in high school, and began to absorb all kinds of music as a listener, from classical to pop to jazz. It was too late for me to become a professional musician (to have the right technique, you have to start at the age of 10 at the latest), but I knew I had to stay as close to music as possible, so I became a musicologist.

You spent three trimesters studying at the prestigious Paris Conservatory with an Erasmus scholarship. How much impact did that experience have on you and your career?

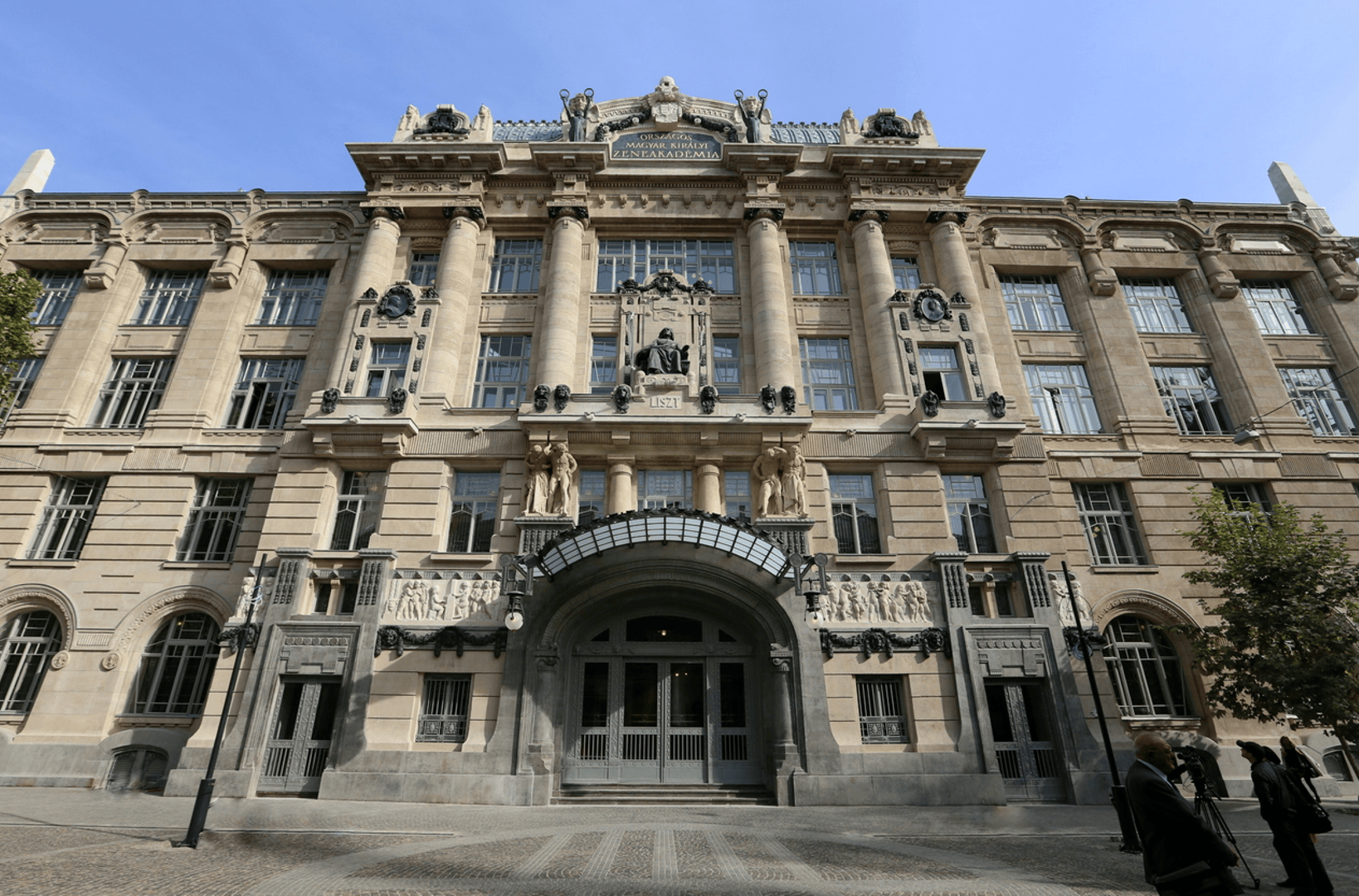

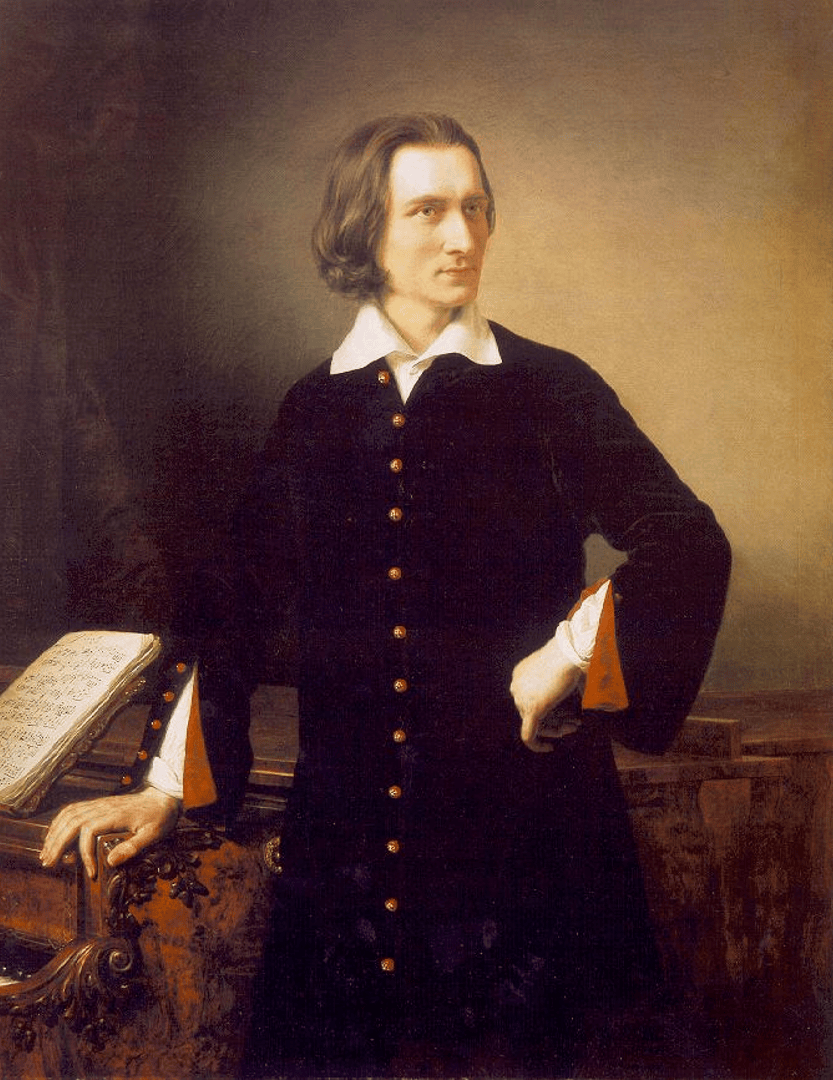

Although the impetus for my application for an Erasmus scholarship as a student at the Liszt Academy was very personal (at the time I was in love with a girl who was going to Paris to study), it became one of the most important professional experiences in my life. I always tell my students to go abroad and then come back. Both are important. You need to leave your home country to have new experiences, learn about other cultures, to gain a new perspective on yourself, but then you need to take all your experiences back to your home country, which becomes different as a result. Distance creates understanding. My professional career was influenced in two ways thanks to Paris: I learned French and translated all the writings and interviews of the great French composer Claude Debussy into Hungarian, which was published as a book much later, in 2017.

You have been giving lectures regarding music since 2003. What makes you so committed to teaching?

In academia, there are two basic types of scholars: those who are more inclined to research and those who are more dedicated to teaching. I belong to the latter category. Of course, there is no black-and-white, nor should there be: students can benefit greatly from meeting great researchers, and those born to teach must do research to avoid the risk of becoming superficial stand-up comedians on a particular topic. To me, teaching is the most beautiful thing in the world. You get excited about something and share that enthusiasm with others. I believe in two things: first, that any subject can be interesting, and second, that the most important drive in teaching – I know it may sound corny – is love. If you do not love your subject, if you do not love the students, and if you do not love the situation of imparting knowledge, then it's not going to work and it's not worth it. One of the wonders of teaching is how much you learn as a professor in the process. The first sentence of the textbook on harmony by the great 20th-century composer, Arnold Schoenberg, reads as follows: "This book I have learned from my pupils." I have been teaching for 16 years and feel that I have learned as much from my students in those years as I learned from my professors in the decades before.

Between 2017 and 2018 you taught at Bard College with a Fulbright scholarship. What was it like to teach American students? Did they know anything about Hungarian music and culture?

Besides my year in Paris, the greatest professional and personal experience of my life was the year I spent with my family at Bard College in Upstate New York. The Hungarian educational system is quite different from the American one, so the knowledge, experience and expectations of American students are also different from their Hungarian counterparts. For me, it was a life-changing experience. Hungarian professors and students follow the German model, which they inherited from the 19th century: for them, knowledge has something to do with the amount of information you have in your head. You have to acquire a lot of data about the world, so Hungarian students know a lot more information. They know much more about America than an American student knows about Hungary (of course, this has to do with the importance and the real and metaphorical size of the two countries). But on the other hand, this data-based knowledge is not really useful. Hungarian students can not really argue, they are afraid to ask questions because they fear being ignorant. For the American student, knowledge has nothing to do with data: it's about skills. I loved at Bard College how brave they were to ask questions about topics they knew virtually nothing about. Their argumentative skills were also amazing. The ideal for me is somewhere between the two extremes, a little closer to the American model. It's great if you know a lot of data, but if you can not express yourself, if you can not start or participate in a conversation, then that knowledge is useless. To your other question, the students at Bard knew something about Hungarian culture, but in that respect, Bard College is a special place because, thanks to the late László Bitó, an alumnus and patron of the institution, quite a few Hungarian students study music there, so Hungarian culture is more present there than in other colleges in the United States.

What is unique to Hungarian culture and classical music? What differentiates it from Austrian, Czech, or any other type of classical music?

Hungarian classical music was born in the 19th century, but its great period is the 20th century. We have some composers like Béla Bartók, Zoltán Kodály, György Ligeti and György Kurtág, who are considered the greatest among the greatest composers. In the world of classical music, Hungary is a much more important country than in any other field. It is difficult to say in a few words what makes Hungarian music so special, but I think it is three things: its relationship to the great classical tradition, its innovative spirit, and the way our beautiful and very special folk music is used in it. Using Bartók as an example, we can see what I mean: As a pianist, he was a great interpreter of the music of classical masters like Bach, Beethoven, Mozart and others, but as a composer, he was one of the most innovative spirits of his time. But this innovation was not one hundred percent new: it was based on music going back hundreds if not thousands of years, music preserved by peasants in the countryside. Old and new were thus blended into a new quality. Hungarian music is a musical universe where things of different origins can live together without harming each other, so it represents an ideal world. Something we should try to imitate in our daily life.