In his webinar, Professor Miklósi showed how ethology, the scientific study of animal behaviour, can help the development of social robots. He also presented the case study of Biscee, the social robot, that he and his team develop at ELTE in collaboration with the engineers of the Budapest University of Technology (BME). Read the interview with him, originally published at the website of the Alumni Network Hungary.

The field of ethology might not be familiar to many. What exactly does an ethologist do?

Ethologists study the behaviour of animals and humans. They focus on the question about function, that is, what is the function of a specific behavioural trait and how does it contribute to the survival of the individual and the species. They also study how environmental stimuli, both from the physical and social environment affect behaviour and what kind of mental and neural mechanisms control the behavioural output. Many ethologists are typically working in the nature on free-living animals, and observe their behaviour over many years. However, many scientists prefer to run investigations in the laboratory where they have better control over the environment and also the animals. These two methods are complementary, and in the end, we hope to get a clearer picture of the mental and behavioural abilities of animals.

How did you become interested in ethology? Why did you choose this scientific field as your profession?

I was always interested in animals (and humans) because I wanted to figure out what they do and why they are doing it. Furthermore, it was and still is an exciting question: What might go on the animals’ minds, and how they differ from us? In the beginning, I was studying fish behaviour, later worked on chicks. About 25 years ago we started to investigate dogs because they seemed to be very specific kinds of animals. Our main question was how could domestication ‘produce’ an animal species that so well into human societies and families. What kind of features make the dog being a ‘friend of people’?

You coined the term ethorobotics. What does this concept mean, and how does this work in practice?

Many years ago, we started to work with engineers who asked us for help in designing social robots which can interact with people. I found this possibility very challenging and we suggested that the human-dog interaction can be a useful model for designing successful social robots. However, in practice, things became more difficult because this modelling proved to be difficult for engineers and programmers. So we had to teach them a bit of ethology, and they had to understand some basic rules of animal behaviour. This situation gave me the idea that it would be worth establishing a kind of interdisciplinary field of science that provides a bridge between roboticists and ethologists. Ethorobotics mitigates the application of rules of animal behaviour for designing embodiment and behaviour in social robots. So engineering problems will be approached by solutions that have been evolved in natural systems.

How and in what fields can social robots help humans? Do we really need them?

There are many ways how social robots can help, however, they are not ready for these tasks. Much research and industrial development are needed before such robots will be put to work in large numbers. There is no question that social robots will have to work in the future because there are many jobs where humans need help, or there could be replaced fully. For example, such robots can help waiters in coffee shops or restaurants, they can also be useful as assistant nurses in homes for the elderly. The problem is that these robots are very unreliable, that is, they break down regularly. In addition, their skills are also limited, so in sum, they do not provide a net benefit for the users. In my view, we need 5-10 years before social robots will provide useful services for our communities.

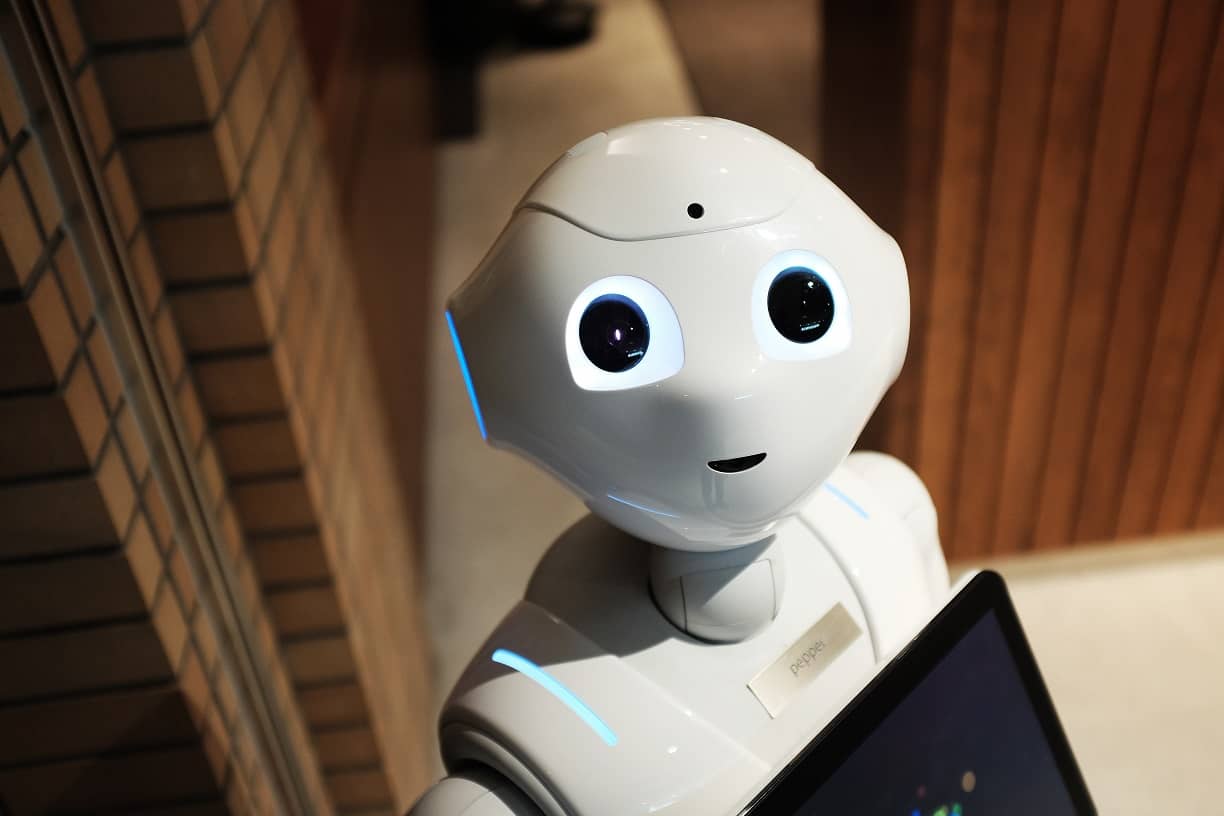

What kind of characteristics and design should social robots have, so as humans would perceive them as friendly and not scary?

Adult humans are used to seeing robots in films, so ‘typical’ robots, like R2D2, should be perceived as being cute. People are more afraid of robots if they look very much like humans, or some strange animals or monsters. So the first task of the designer is to make the robot look friendly. Behaviour can also enhance the acceptance of social robots. Slow-motion, avoiding direct physical contact, short looks at humans are a few examples to make the robot friendlier. It is also useful if the robot can detect when a human does not want to engage with it and shows avoidance before a direct encounter takes place. But in the end, humans should gain positive experiences through interaction with the robot.

Your team develops a social robot at ELTE, called Biscee. What is the aim of this project? At what stage is this project currently at?

This project is based on a real scenario in which social robots act as waiter assistants. There is a restaurant in Budapest where robots also help serving food and drinks. We aimed to make an even better waiter assistant that can get into simple interaction with the guests. So people may enjoy more eating and drinking at this place but they could also engage in our ongoing research to find out what behavioural features of Biscee make it more attractive. Biscee can look at people sitting at the table by turning its head, and it also emits various sounds when greeting the guests or saying them ‘Good bye’. Importantly, Biscee is not using a human-like voice. Using specific software, we designed an artificial sound kit that grants the robot unique vocalisations.

When and where can we meet Biscee?

When and where can we meet Biscee?

Biscee is at the moment in our department. The pandemic hindered our efforts to finish building and development, so we are still at the experimental phase. However, we are running behavioural tests to see how people react to Biscee’s behaviour. So we invite volunteers and they can eat a pizza at our ‘experimental restaurant’ served by Biscee. We are aware that this is not a real situation but this experience will be important to prepare Biscee for working at an actual restaurant. We hope that Biscee will not only amuse the people in the restaurant but also help the waiters, so they can spend more time with the guests and do not get so tired at the end of the day.

The Alumni Hungary Webinar Series feature outstanding Hungarian scientists and professionals presenting their fields of expertise. To read the previous interviews with architect Samu Szemerey, click HERE, https://alumninetworkhungary.hu/magazine/news/smart-cities-future-cities-interview-samu-szemerey

and for the interview with biologist Csaba Pál, click HERE: https://alumninetworkhungary.hu/magazine/news/fight-against-antibiotic-resistance-interview-biologist-csaba-pal.

The webinars are only available for the registered member of the Alumni Network Hungary. To become a member register HERE. https://alumninetworkhungary.hu/user/register