The works of Kertész are focused on the research of personal freedom and choice in the face of totalitarian regimes. Its recurring themes are the Holocaust, loss of language and identity. At the age of 14, Kertész was deported with other Hungarian Jews first to Auschwitz and was later transferred to Buchenwald concentration camp. Although most of his oeuvre draws inspiration from this experience, his work goes beyond the horrors of death camps, aiming to understand the limits of human communication by exploring the unspeakable and the inexpressible as well as the possibilities to compromise between people of opposing beliefs.

New literary approach

His most famous novel, Fatelessness (1975) follows the story of a Hungarian teenager, György (Georg) Köves witnessing his family’s deportation to Auschwitz, then two weeks later losing his freedom, finding himself sent to the same concentration camp. Written in a bleak, matter-of-fact tone, with the protagonist drifting through the events rather than actively interpreting them, the novel documents the boy's life in the camp and the vacuum he finds upon returning to those who have never left.

Although some elements of Fatelessness can be interpreted as autobiographical, Kertész clearly distances himself from the narrator, stating that the simple wording of his novel is an artistic choice rather than the direct result of recalling his own teenage memories. The relevance of Fatelessness can be seen through this unique and bold linguistic approach in describing the life in concentration camps through a tight, distancing objectivity but with an unexpected touch of openness, irony, and humour to it. The style draws from the realization Kertész made as an adult, that living in dictatorships deprives people from a more complex thinking and leaves only this childish language to express oneself.

A film sharing the same title was released in 2005, the script was also written by Kertész.

Living and writing the same novel

Following Fatelessness, the novels of Kertész explore the connections between language, memory and identity, trying to incorporate experiences of the survivor (as well as the guilt that comes with it) to forge them into a personal destiny. “Kaddish for an Unborn Child” (1990) and “Fiasco” (1988) are often read in a trilogy with Fatelessness. While Kaddish is a furious monologue against the thought of bringing a child into a world that enabled the Holocaust, Fiasco revisits Köves, now a young adult returning to Hungary after the Stalinist government has taken over. The short novel The Pathseeker (1977) examines how memories of the past can be conserved and their implications on the remembrance of the Holocaust, while Detective Story (1977), a Kafkaesque prison confession explores how all oppressive regimes have similarities between them.

Continuously exploring memory and identity by merging the roles of writer, narrator, character, novel and life, Kertész eventually comes to a conclusion that memories are impossible to transmit: as soon as he writes them down, they cease to exist as his own personal history and become part of an artistically curated archive. His style, cynical, avoiding pathos and self-pity, yet full of humour shows the reader the moral he lived and wrote by: in Kertész’s world, the ideal person is someone who creates and recreates themself freely and endlessly, never giving in to defining themselves through ideologies.

The works of Kertész were translated to most world languages. You can read excerpts from Fatelessness in English, German and Swedish on the official Nobel Prize website - or should you like to chisel your Hungarian skills, you can also find his entire work in the Digital Archive of the Petőfi Literary Museum too!

Links and sources: MEK ; konytar.dia.hu ; reader.dia.hu: A nyomkereső , A kudarc , Kertesz Imre; newyorker.com ; GoogleBooks

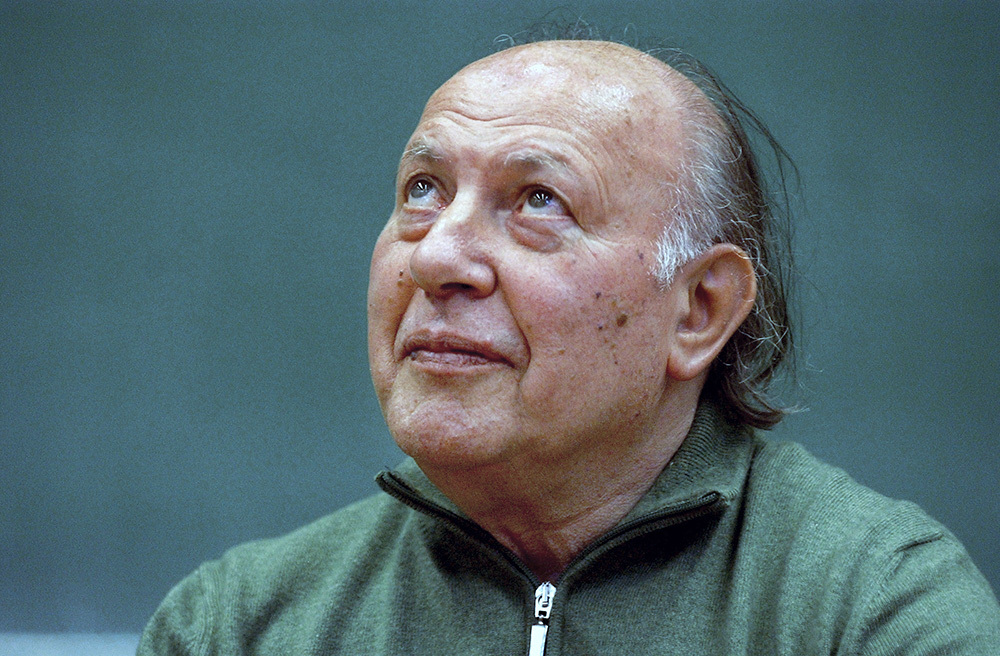

Source of the picture(s): Wikipedia